Ukrainian families dream of budgeting. But they don’t do it. Why?

- Maryna Pedko

- Sep 11, 2025

- 4 min read

As part of one of our projects, we at Lanka.CX decided to explore how Ukrainian families manage money in their everyday lives.

We studied not the numbers, but the habits and logic of actions: who makes financial decisions in the family, when, and how.

It turned out that most families do not have a consistent practice of joint budgeting.

At the same time, they genuinely want more predictability, less stress, and more agreements.

The chronic difficulty is that this kind of control is hard to organize.

Sounds like a market opportunity.

So the idea came up: what if we created an app that would help them do it?

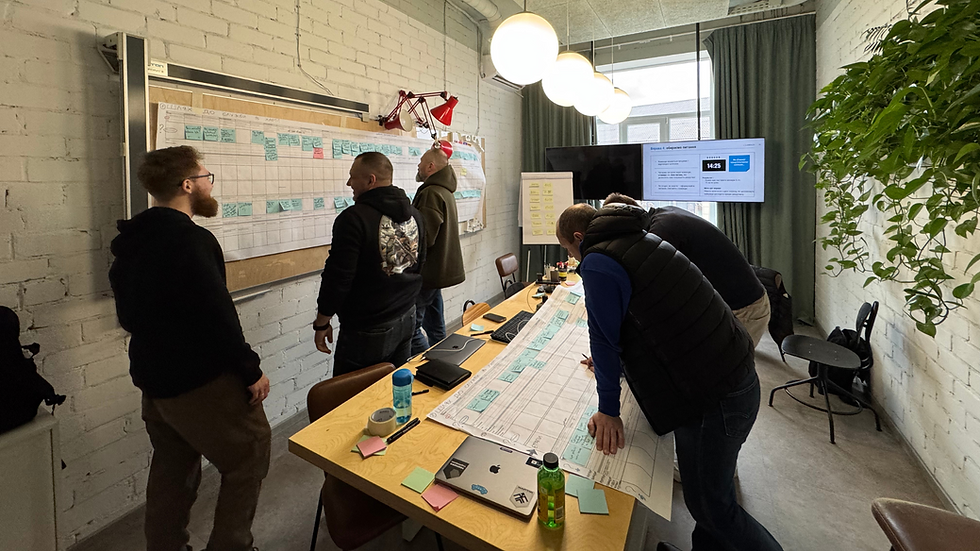

In less than an hour, we created an AI-generated prototype of the app — minimalist design, basic functionality, key scenarios.

We brought the prototype to user testing, and all respondents said the idea was great — the app was convenient, useful, and logical.

But when we started asking deeper questions, we got a unanimous response:“Well, it’s not for me, but it could be useful for others.”

It was disappointing to admit: the prototype passed the test, but didn’t spark any real desire to use it.

The fact that people like your idea doesn’t mean they’ll actually use it.

And that’s when it becomes important to take a step back:

What exact problem are we trying to solve?

Is the customer really trying to solve it on their own? Or do they need help?

How are they addressing this need today, and how might we become part of that solution?

How families in Ukraine actually manage their money

Lanka.CX consultants Oleg Balakin and Tetiana Buts conducted a series of in-depth interviews. They didn’t talk about apps — they talked about everyday life: how people manage money in families, how they divide it, how they try to save. What helps them distribute expenses so that, at the very least, there’s enough left to get through the month.

They discovered several vivid models of financial interaction within families.And it’s these models that determine which services families will respond to — and which ones simply won’t fit into their lives.

«We decide everything together»

These are families where the budget is technically split across different cards, but functionally shared.

Money is transferred, cards are handed over, agreements are made. There’s usually a shared notebook, spreadsheet, or budgeting app.

The main challenge is that often only one partner has full visibility over the finances.

To understand how much money is left by the end of the month, they need to ask, calculate together, and remember who spent what.

«Split responsibilities»

Each partner manages their own money and covers their share of household expenses.

One pays for the child, the other for daily needs. In some cases, they might not even know each other’s income.

This setup works until there’s a need for a joint large purchase or when one partner loses income.

Such families often face social judgment: “How come you keep everything separate?”

«The Manager»

One person distributes the money — and it’s not always the one who earned it.

They know how much is left, who needs what, and what to spend on. The other partner doesn’t necessarily need to get involved.

Fees for card-to-card transfers often push these families to use cash.

When everything depends on one person, it becomes hard to plan without stress or avoid dipping into credit by the end of the month.

«There’s enough for everything»

A high income allows some households not to count every penny.

One partner can transfer a large sum to the other — and not ask what happens next.

But when there’s a need to save more, problems arise.

Without visibility into how money is spent, it becomes difficult to manage it effectively.

Why do families want to budget — but still don’t?

Not everyone sees the point: “I already know how much I’m spending.”

There’s no convenient way to coordinate in a couple or family.

Budgeting often feels like controlling each other — not supporting one another.

Services don’t account for the everyday household logic that families actually live by.

What’s important to take away from this?

Just having matching cards doesn’t guarantee a shared budget.The desire to track expenses doesn’t equal the readiness to plan ahead.And most family decisions aren’t really about money — they’re about trust, roles, and agreements.

That’s why financial products shouldn’t be tested only as UX interfaces,but as services designed to fit into real life.

The AI prototype we created showed — just in time — that the idea didn’t work in a real-world context.From there, we moved into research, segmentation, and a strategy built on actual behavior.

Prototypes aren’t for confirming ideas.They’re for seeing what’s missing for the idea to truly work.

Lanka.CX is always open to helping you test your idea —and take a step back together, if that’s what the idea really needs.

Comments